Peter Rubin once said, "Inspiration is the thing that happens between thoughts." He must have a lot of thoughts.

Most concept artists have transitioned from traditional media like ink and paint to digital, but Peter Rubin was the first freelance artist to do it. He's worked for over seventeen years in the industry working on films like

Independence Day (1996),

Gangs of New York (2002) and

Green Lantern (2011). His four-year work as an art director at George Lucas' Industrial Light and Magic led to him becoming a "go-to guy" for directors like Clint Eastwood (

Space Cowboys).

I first saw the work of Peter Rubin from

Battlestar Galactica: Blood and Chrome which was also featured by Blastr and io9. His image of the Cylon snake (nicknamed "Cython") was so striking Blastr said it had to go in.

Here's an exclusive interview with him and he talks to me about the challenges of an artist in the entertainment industry and the joy. Plus, he tells a great story about designing the new chest emblem for the Superman reboot

Man of Steel.

[Image: Terminator 3: Rise of the Machines (2003)]

Q: When someone asks you what concept art is, what do you say?

It's the very first visual representation of a film (the same could be said of storyboards, although they have a different purpose and origin). It brings a film's creatives together, mentally, into the same pictorial space. It provides producers with the confidence to underwrite the process, directors a method of communicating their ideas, and designers with the first iteration of the assets which will become the gears of the narrative machine.

Q: What's it like being an artist in the entertainment industry?[Image: Hulk (2003)]I don't have any real experience of being an artist in any other arena. I have heard artists I respect call it the dead-end job from hell, but I don't feel that way at all. I haven't acquired the cynicism somehow.

It's both as mundane as any other job and as glorious a thing as I can think of. It can feel more like play than work, or it's dull, or it's terrifying. You don't know which it's going to be on any given day. It's easy, and it's impossibly hard. I draw pictures on a screen, it's not exactly digging for coal; but I have once in while nearly worked myself into the hospital.

So much money rides on these things, and at the same time - it's only a movie, right? How much could it matter? But it's our livelihood and our great love, and I see people implode over it all the time.

From a practical standpoint: I don't live in Los Angeles, but I try to maintain some kind of presence there. I think my career would have been an easier thing to manage if I'd gone back there after my first couple of projects at ILM, but my family and I fell in love with the Bay Area. So I have to do some commuting. But so many films being made outside of California means that even if you live in LA, you have to be prepared to travel.

With the new technologies, it's easier to live away. A lot of artists work out of their homes, even locally. But I love being on-site, in the art department - the mix of personalities and methods, you learn so much; and there's nothing like direct access when you are working for intensely creative people.

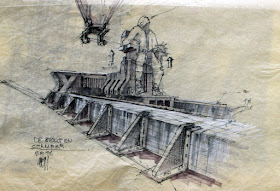

Q: Recently, your concept art was released in connection to Battlestar Galactica: Blood and Chrome where did the inspiration for the designs come from?Well, from the script, of course; but mostly from discussions I had with the show's producer, director and writer, and from their need to have an art package in hand VERY quickly. There was no time for refinement, though we did the best we could.

After I did the initial concepts, we sat around a table with the VFX guys for a couple of weeks and hashed out a lot of stuff. We took inspiration from the show, of course, but also from other films, from existing architecture and landscapes. We did some of that "no, no, that looks too much like the creature from (insert genre movie title here)," as a way of winnowing out certain things.

The robot design - the one that looks vaguely like a centurion of some kind, with one eye - was a little unusual in that I had done it on my own as a portfolio piece, and David Eick saw it and liked it - he bought it from me. And I have some more environment work that I'd love to put on my site, once they show it.

Q: Are you disappointed that BSG will be a web-only series?Certainly. I loved working with those guys, and I'm a huge fan of the show. Honestly, though, the whole proposition of doing a live-action series without any sets, all-CG environments, and doing it on a TV budget, is in my mind a dicey one. It's hard to make it work convincingly even when you have all the money in the world. Nevertheless, their VFX team is extremely talented, and I heard the show was looking very good. I wish them luck, and I hope they make it on the air eventually.

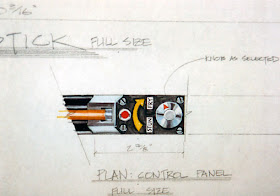

Q: The illustrations for Surrogates (2009) are incredibly detailed, including explanations of the technology and cross-sections. How important is it to have a technical understanding of the designs you create?It's part of my process; it's very important to me. It probably doesn't mean as much to most of my clients.

I'm actually more story-oriented than design oriented, in a way - that's what interests me. Not just what looks cool, but what does it mean in context?

When I'm working on a project that involves world-building, I try to immerse myself in it, and answer my own questions about it, solve problems brought up by the technology or the requirements of the story. The

Surrogates stuff came out of my having a very different concept of how the robots would work than the one being promoted by the production designer, who had come onto the project later than I.

He thought that the Surries' faces should be operated through hydraulic bladders under the skin, filled with some kind of icky green liquid, whereas I was operating under the assumption that it was more about mechanical servos moving foamed silicone or the like. So I started doing some research into how artificial muscles actually work, and tried to come up with a plausible technology that blended the two approaches. Once I assumed that the robots were full of green juice, then I had to figure out how that would translate into things like body temperature, skin color, and major muscle movement. It was pretty successful, I thought, but it was never really used in the film; our VFX budget was slashed to the bone.

There are a few people I've worked for who have a very cerebral approach to the work, which matches my tendencies. Alex McDowell, the production designer on

Man of Steel, is a bit like that.

Q: You were the first illustrator to switch to all digital back in 1992. What was it like transitioning from traditional media back then?[Image: Terminator 3: Rise of the Machines (2003)]

I got very interested in CG in the late eighties - my brother-in-law was a graphic artist who worked on a Mac, pre-Photoshop, designing icons for some of the first color GUIs. He showed me his stuff and I immediately started thinking, "how can I incorporate this into my work?" - and it just got more intense. I did my first digital art on an original black-and-white Mac classic, with a mouse, drawing pixel-by-pixel.

Then Photoshop came along, and Painter, which is still my daily bread-and-butter app, and the Wacom tablet. But I didn't actually make the transition until I had felt like I'd mastered it. I was working on a show that had a Mac-centric crew, very rare in those days. The PAs even had computers on their desks, which was unheard-of. I let the UPM know what I was planning to do, and this guy, a power-user who was scanning and storing storyboards digitally and programming databases to organize them, told me I was crazy - that I couldn't pull it off. I went out to a long lunch, bought my first computer, and was doing digital art that afternoon, actual production art. He changed his mind.

The surprising thing at the time was that many of my fellow artists were vehemently opposed to it. I tried to evangelize a little, but was seriously rebuffed. They were afraid of it. A few of them still are. There were some who were applying the technology in partial ways - one might be scanning boards, which I already mentioned, another creating certain types of graphics or signage in Illustrator, a third building 3D models to use as design tools. But I was the first one to throw away my pencils for good, and all at once. My clients, who I thought would be a tough sell, fell in love with it right away.

Roland Emmerich was especially helpful - I went to him and said, "OK, I'm drawing pictures for you, but I think there's a ton of things I can accomplish with a little more tech on my side. Laser printers, 3D software, scanners, and the like." He went for it, and we shared the cost. That was for Stargate. I did 3D storyboards, which were eye-opening, and temp VFX, and video-playback animation, and color comps, and pre-vis... I was on it for over a year. I shared an office with him, at the end, and he could just look over my shoulder and tell me what he wanted. Kind of awesome.

Q: Where do you see digital art changing concept illustration in five years?The process that's going on now will continue - there's a lot of pressure on free-lance artists to be up on the latest software and to own the latest gear, and to be multi-discipline. The technological pipeline for concept art will become slightly more standardized, the way that traditional set design has been standardized for years, for the sake of simplifying the communication and the process. We need that; so much time is wasted trying to get all the different packages to talk to each other, and translate files. How we do that and keep the costs in line for artists and for studios both, that's the big question. Plus, how do we simultaneously allow for experimentation and variety, which as creatives we also need?

More VFX methodology will creep into pre-production. Distinctions between job descriptions will continue to be blurred by the technology, as the methods grow and change. This is very problematic for the various intra-guild job classifications, which is how base salaries, and therefore labor budgets, are determined. Pre-vis artists have been incorporated into the process, for instance.

There's a job we have, to persuade certain people that what we do is still central to the process - it seems like a no-brainer, but some productions are attempting to short-cut the design process out of existence, to work without a real production designer, and they feel like digital technology is a path to doing that. It's foolish, both from a creative and from a financial point of view.

My opinion is that the narrative art is best served by a fully integrated, interactive and aware creative team, from beginning to end. We start with concepts, turn those into assets, then it's a process of iteration and refinement. A lot of the reason so many genre pictures are aesthetically unsuccessful is that so much of the creative process in films that are heavily CGI-dependent is shucked off to wholly separate entities - groups that don't ever meet, much less effectively interact. It takes an extraordinarily strong director to shepherd that many disparate individual forces into a coherent vision - and an extraordinarily conscious and involved VFX supervisor and facility to meet the director and designer halfway. And good, solid design as the through-line.

In the short term, the biggest changes to film design will come out of technologies like 3D printing and digital manufacturing.

Already, it's possible to take concept art, such as digital sculptures of the sort I do all the time, and, using stereolithography or CNC, turn them into set pieces with very little alteration. In five years, this will be old-hat. There may be a lot more 3D - and I mean stereoscopic 3D - concept art, depending on the success of that medium. I've already done some myself, envisioning environments for a film that didn't make it into production. (I know that 3D is supposed to have a questionable future right now, but I think it's here to stay.)

What other technologies might come along in the next five years - or even three - will be very interesting to see.

Q: What are the three biggest influences in your art and why?Can't pick just three - sorry. I'll give you four categories, that's as narrow as I can make it!

1. The comic strips, and their creators, that were my first inspiration. George Herriman. I loved Walt Kelly and Charles Schulz, and learned to draw by imitating them, and the comic book artists. Curt Swan, Neal Adams, Jim Steranko, Jack Kirby. Mad magazine - Jack Davis, Mort Drucker, Wally Wood. Political cartoonists and editorial illustrators like Pat Oliphant and Al Hirschfield. Jules Pfeiffer influenced me a lot, both with his comics and his love for the medium.

2. The movies next, Disney and Harryhausen when I was a kid, then Kubrick and Scorcese and Welles; Robert Altman; The Marx Brothers; I watched

Casablanca again and again when I was thirteen. I loved Rod Serling.

Planet of the Apes was huge for me,

2001 came along about the same time; those two movies are probably responsible for my having a career, in a way - they are the reason I got interested in film production. I was making latex ape masks in junior high, from scratch.

3. Later, it was the film artists that I worked with. Directors, production designers - most of all my fellow illustrators. Even later, the artists I worked with when I was an art director at ILM. Even the ones who were much younger than me... I would never have admitted it then, but keeping up with them was murder.

4. Most of all, I think, the written word. I was a precocious reader - I was reading at a ninth-grade level when I was about eight, I was told. I loved Edgar Rice Burroughs, Arthur Conan Doyle, Mark Twain, Poe, and almost any science fiction I could get my hands on. Ray Bradbury was very important to me, so were Heinlein, Sturgeon and P.K. Dick. A. E. Van Vogt. Tolkein, of course. I read the Bible from cover to cover. Shakespeare.

Star Wars came along when I was almost an adult; it just confirmed everything I had learned from those writers. I loved it, wholeheartedly.

Q: What can we expect next from you?Well,

Man of Steel comes out in 2013. I've left some fingerprints on that. I spent nine months working with Alex on the details of Krypton. Like I said, he's a thinker... for him, it was all about the aesthetic and the culture of these aliens - characters that everybody thinks they already know, which made it all the more challenging. He was very particular, which drove me to work hard to try master the style he had in mind. It stretched me, and I think we did some new and interesting things, both from a visual point of view and also technologically, within the process. Zack is a strong director, too, and I'm very excited by what he's bringing to the story. What we did behind the scenes is going to have repercussions in the business, and on screen it's going to knock people's socks off, in my opinion.

I'm a huge Superman fan going back to childhood, and so was very, very glad to be a part of it. I got some amazing design opportunities. For one, I was asked to design the new "S" insignia, the one that Henry Cavill is wearing in all those

leaked on-set photos. I've been drawing that in one version or another since I was four years old. I was hitting in the sweet spot, and it felt like one of the high points of my career as a designer. There were some interesting struggles associated with it - I'll tell that story someday. :)

I've been doing some work on

The Host for Andy Nicholson, based on a Stephanie Meyer novel, directed by Andrew Nichols. There's a book coming out next year that's kind of hush-hush, but I have some art planned for that. And I have a project of my own that I'd like to get off the ground - a short film with a robot theme that I've managed to get a couple of people excited about. We'll see what happens!

Thanks for the interview Peter!

You can see more of his work at his website

http://ironroosterstudios.com/ and right here on

my blog in the future.

Read more of my exclusive interviews with the people that create the magic

in my list of interviews.

What do you think of Peter Rubin's work? After working on the ground-breaking special effects for Star Wars, Ralph McQuarrie and production designer Ken Adams were tasked with bringing another science-fiction powerhouse to the big screen: Star Trek: Planet of the Titans.

After working on the ground-breaking special effects for Star Wars, Ralph McQuarrie and production designer Ken Adams were tasked with bringing another science-fiction powerhouse to the big screen: Star Trek: Planet of the Titans.